External Author – Patrick Hottle

Note that this tutorial is not my own work, but was developed by the reasonably rational Patrick Hottle and is hosted here for convenience.

Intro

There are five primary material types that DBF (Design-Build-Fly) uses when fabricating RC planes.

- Foam (foam board, polystyrene)

- Wood (balsa, basswood, etc.)

- Composites (fiberglass, carbon fiber)

- 3D Printed Plastics (PLA, TPU, etc.)

- MonoKote

While it is certainly possible to build an RC aircraft out of any single material listed above, Declan’s amazing Spruce Goose recreation and the countless foam-only planes in the DBF space highlight how fragile and time-consuming the process can be. This is why nearly every past competition plane has had some combination of the four material types listed above. In the case of the 2023 competition plane, every material type was used (except MonoKote), and each material was chosen for a reason and served a different purpose. Throughout this tutorial, I will be highlighting the three primary things to consider when selecting a material for your aircraft’s design:

- Weight

- Strength / Durability

- Manufacturability / Cost

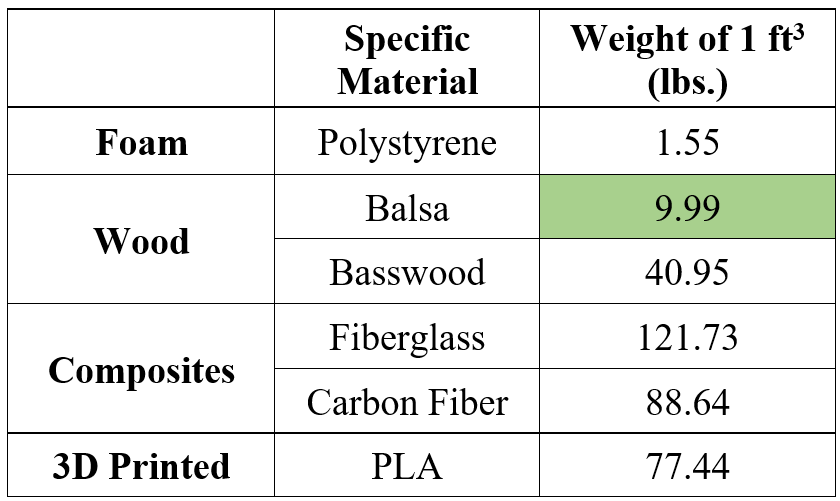

Weight

Weight is often the most difficult and easiest to neglect side of RC aircraft fabrication. Simply put: the lighter an aircraft is for any given planform area, the better flight characteristics it is capable of. To learn more about this relationship with stability, see Aircraft Design Tutorial. Because of this, you always want to make your aircraft as light as it possibly can be with smart material selection. Unfortunately, optimizing an aircraft to be as light as possible comes with many tradeoffs related to cost, time to manufacture, and, most frequently, strength. For many materials of a given density, lighter also means weaker. This is why it is important to understand the statics and kinematics of the aircraft you are designing, so as to avoid over-engineering and making the aircraft heavier than it actually needs to be while still being confident your plane won’t fall apart mid-flight. For comparison between materials, the following table shows what each of these common materials would weigh for a given volume.

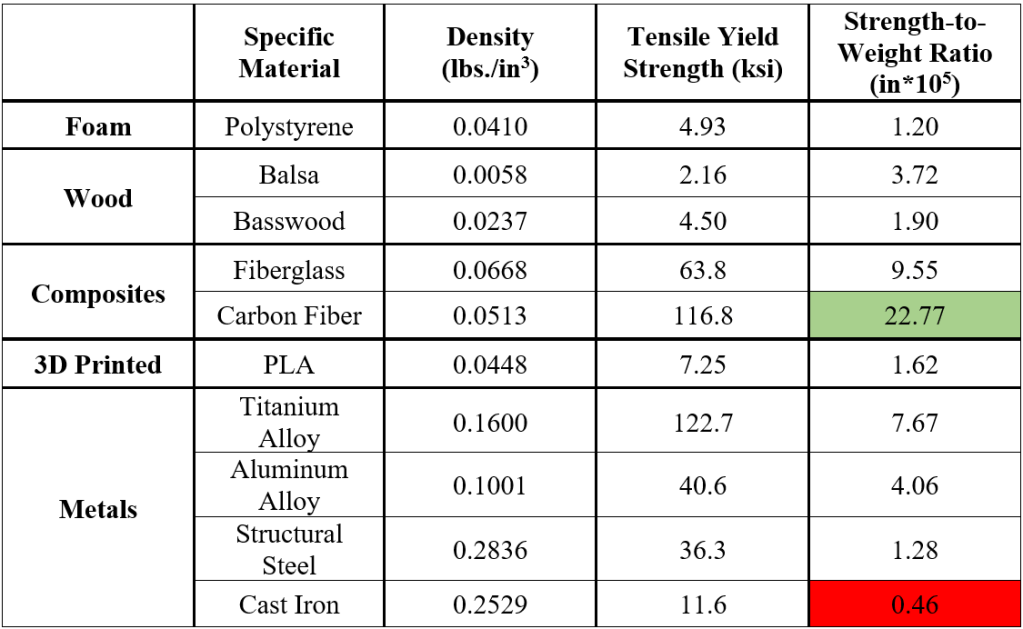

Strength & Durability

Using the above logic, it would make sense to make a plane entirely out of just foam or balsa, right? While we could do this, it would likely be far too fragile to be capable of many of the past mission requirements and would also take a very long time to fabricate with the tools currently available to DBF. This is where strength and durability must factor into our material selection: we need our plane to be strong enough to withstand the lift and drag forces of flight and complete mission requirements, but also light enough to actually fly. Because of this, materials with high strength-to-weight ratios often work best for high-stress areas of the aircraft or any areas that you need to be load-bearing. The following table shows the strength-to-weight ratios for materials commonly used by DBF and also some common metals for comparison.

As you likely could have guessed, it’s not really a great idea to build a plane out of cast iron. Yet, it would destroy the budget and be extremely time-consuming to attempt to make the plane entirely out of carbon fiber. Because of this, the factor of safety of each individual component on the aircraft plays an important role in material selection. The aerospace industry uses a standard FOS of 1.5 for the majority of aircraft components, while the automobile is typically around a FOS value of 3.0. This relatively low factor of safety for aircraft is due to the need for lightweight components and is possible because of the extensive fatigue and failure testing done on all systems as well as rigorous quality control, obviously not something that can be easily done with DBF’s time and budget.

This means that we must be very confident in both the load that each component will experience, as well as the material properties of each component. Because of how we fabricate composite parts such as fiberglass and carbon fiber which are both orthotropic, the material properties quickly become less predictable if the weave is not perfectly laid up. Yet, because of the fantastic strength-to-weight ratios of composites, we can play it safe and go for a higher factor of safety to allow for a bigger margin of error during fabrication. As you can see in Figure 2, the carbon fiber I-beams that the 2023 team designed to use as wing spars were arguably over-engineered with far too high of a factor of safety for our design based on the fact that Preston can easily stand on just one wing without damaging the I-beams. For an example of carbon fiber’s incredible strength-to-weight ratio, just one of those carbon fiber I-beams weighs very little, and is only 2 layers thick, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2: Preston Boling (’23) demonstrating how poorly we calculated the FOS for our wing spars.

Figure 3: Close view of a carbon fiber I-beam used for wing spars.

Manufacturability & Cost

What we’ve essentially learned so far is that carbon fiber is the best material known to man, so why not just make everything out of it? I would certainly agree, given unlimited time and budget. Composites such as carbon fiber and fiberglass are very expensive and take an exceptionally long time to make parts out of when compared to methods such as laser-cutting foamboard and balsa, and 3D printing. Even for geometrically simple parts such as the I-beams, it takes nearly a week to make them after accounting for prep, cure, de-mold, and post-processing time. The fiberglass process is significantly faster and works better when used as a reinforcement method, such as laying the fiberglass around a foam mold to add significant tensile strength to the foam while barely increasing its weight.

Even the fastest to fabricate and cheapest materials cannot be used in any situation. Methods such as hotwire cutting foam blocks can only create relatively simple profiles and becomes less and less feasible on a small scale. Yet, this method works incredibly well for things such as cutting a thin fuselage shell that fiberglass can then be wrapped around (the method used by the 2023 team). This method works well because the foam provides sufficient compressive strength for landing and the fiberglass provides the tensile strength that the fuselage needs mid-flight. The table below shows approximate manufacturing times for example parts and materials, as well as the cost of total materials used rated from 1-5 with 5 being most expensive.